Featured image: Nematodes, pictured inside a sheep on Scottish isle St Kilda. If the immune system has to choose between fighting this worm and malaria, how should it prioritize? (credit: Graham Group)

(Audio note: Unfortunately, this week’s recording is not great. First, it starts a few minutes into the interview, so you miss the introduction; second, a recording issue distorted the quality. If anyone has a better-quality recording, let us know!)

Our guest this week was Dr. Andrea Graham, a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology here at Princeton. She brought us her insight into the immune system, so we dove into the good and bad sides of the cells that usually keep us healthy. Toward the end, I talk briefly about the importance of sea ice algae in the Arctic regions, and how those Northern ecosystems might be in danger if the ice sheets shrink.

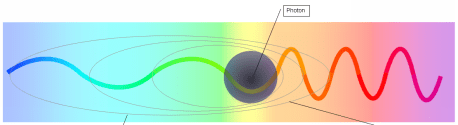

Andrea finds the immune system fascinating. It’s a decentralized system, with no one governing body, so it must deal with problems locally: each cell works independently. When white blood cells gang up on diseases in the body, they communicate their strategies by sending each other small protein messages. These cytokines let nearby white blood cells attack the bacteria in unison; they might also transmit messages globally through the blood stream to share antibody information with the rest of the body (this is how long-term immunization works).

The problem with decentralized systems is that they can overreact by all acting at once. If every white blood cell in the body reacts simultaneously to a new threat, the whole stream is flooded with cytokines. Your immune system’s overreaction causes fever and swelling–and sometimes even death. It’s hard to produce medicines that work against these cytokine storms, since there’s a delicate balance between stopping the immune system from self-harm and preventing it from fighting real diseases. Discovering a medicine that would slow the system gently is “the million dollar question,” Andrea says.

As with anything that has limited resources, the immune system competes with other systems in the body. It takes energy to fight nematodes and energy to reproduce, but sometimes there’s not enough energy to do both. Andrea’s group studied a sheep population, brought to a Scottish Isle centuries ago and left without predators since, to see if real groups of animals have individuals choosing between health and reproduction.

The big breakthrough came when the group found anti-correlations between sheep who reproduced often and sheep whose immune systems cleaned away parasites effectively. In fact, many sheep had healthy worm populations living in the gut, even though the worms were harmful and cost the individual resources. Trade-offs like this mean a great immune system isn’t always beneficial.

Another balance we discussed was having a weak immune system versus to an overly-strong one. White blood cells clump together to suffocate bacteria and other threats, but they can go overboard and clump up more dangerously. These groups of white blood cells block passageways over time, leading to illness. Lupus is one example of an autoimmune disease that acts in this way–and Andrea’s group is looking for correlations between being lupus-prone and having a strong immune system. By joining an existing collaboration that studied the population of Taiwan over time, the group found evidence for that correlation.

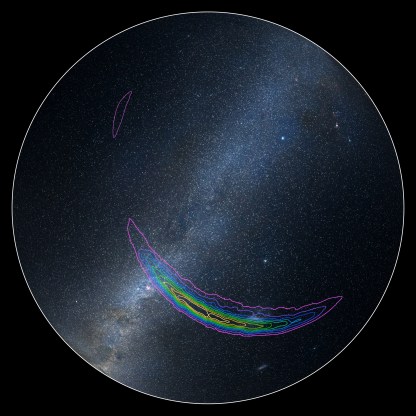

Finally, I ended the show with science news: algae living in the seasonal polar ice caps of the Arctic are crucial bedrock of the Northern food chain. The result comes out of this study from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany. Scientists drew fat samples from tens of species in the Arctic Ocean, tracing the composition of fats in the animals back to sea algae living in the ice. Evidently, 60-90% of the nutrition delivered to herbivores comes from this food source, which is worrying since the ice caps are quickly shrinking.

We’ll be back next week with more, better-recorded radio. Thanks for tuning in!

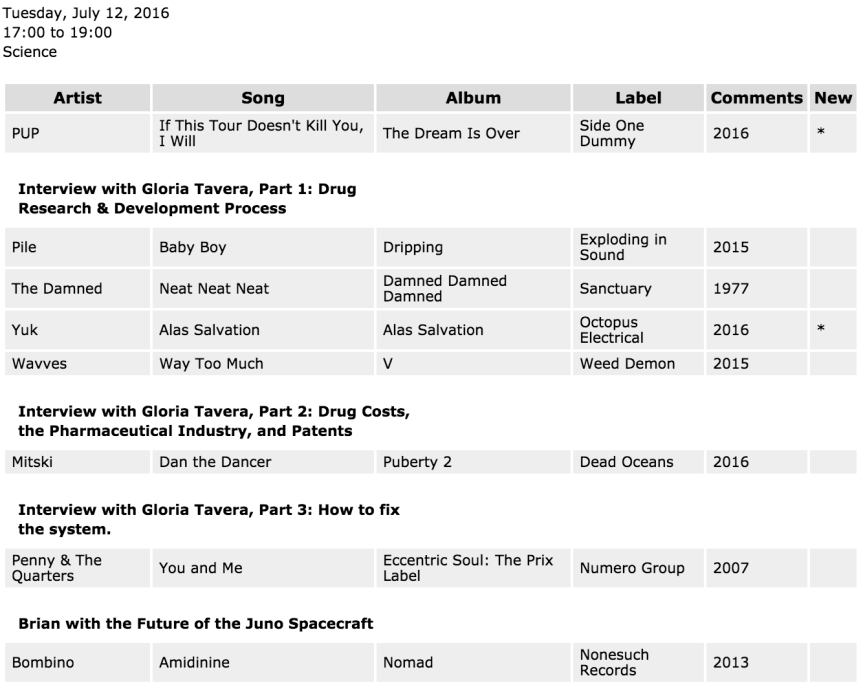

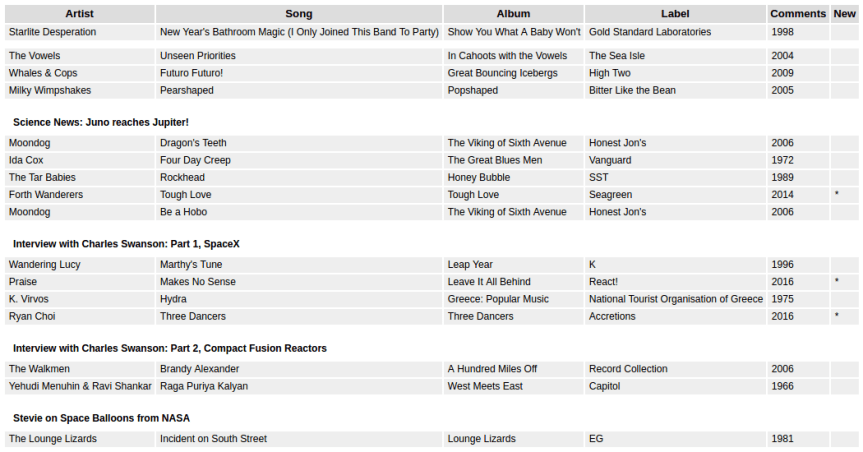

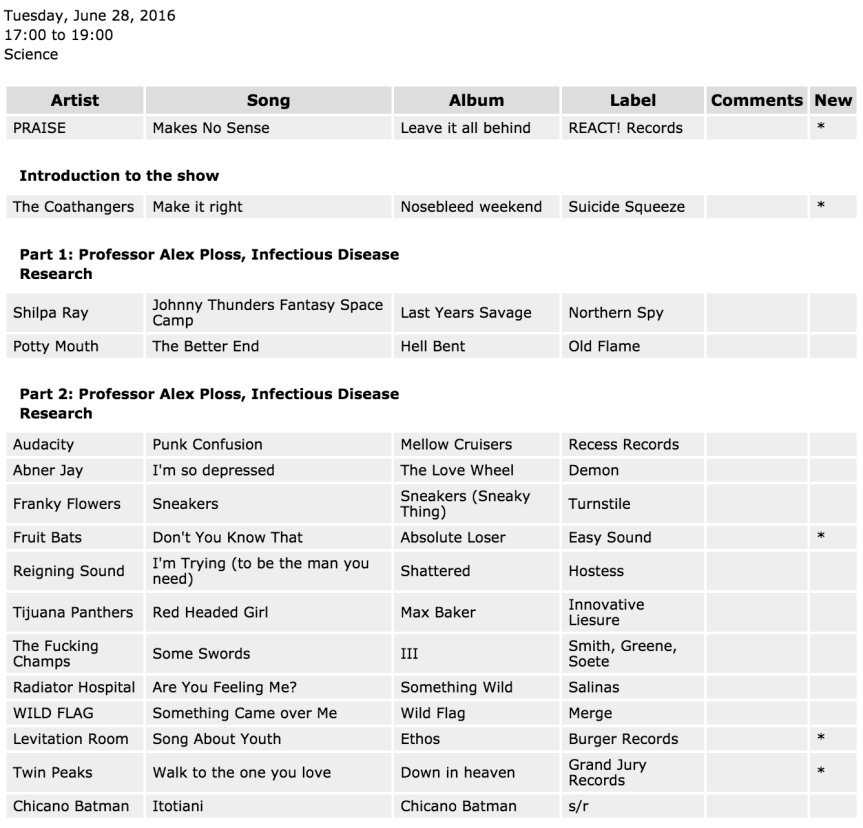

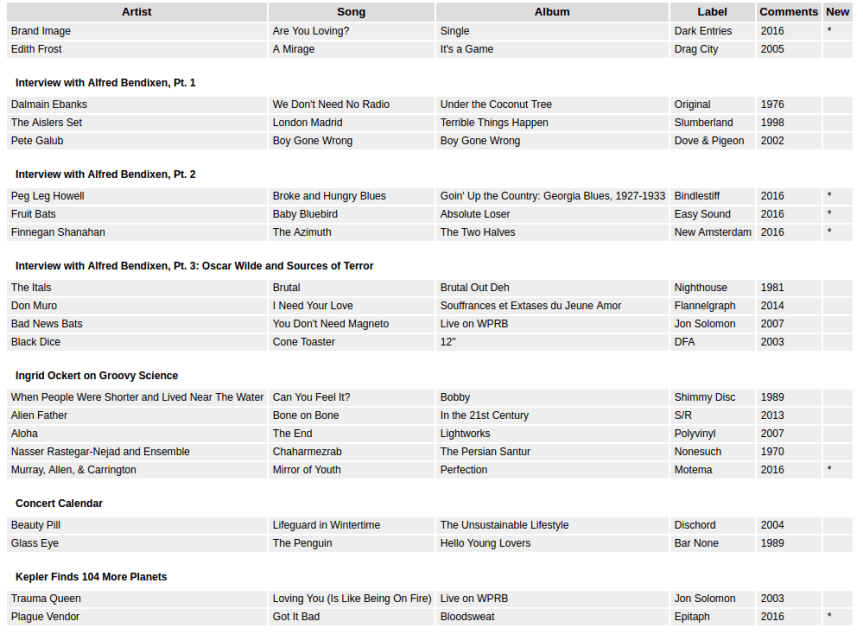

The full playlist is on WPRB.com, or below.

Featured image: Katniss, of the best-selling book/movie series The Hunger Games. (courtesy

Featured image: Katniss, of the best-selling book/movie series The Hunger Games. (courtesy

president of the board of directors for

president of the board of directors for